Anger, identity, hope: American communities wrestle with immigration detention

(Video by Avery Callens and Alexa Durben/News21)

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

BALDWIN, Mich. — Cell service begins to fade a few miles from town, as billboards advertising chain restaurants shift to roadside signs peddling used boats.

Nestled among winding rivers in a stretch of Michigan those in more populous parts call “up north,” Baldwin is a village of just over 1,000 stitched with dirt roads, boarded-up homes and “No Trespassing” signs.

A 25-foot statue of a trout watches over the main drag. And just to the north, pine trees conceal one of the most remote immigration detention centers in the country.

Here, outdoor recreation is both a lifestyle and – along with the private prison – one of the only lifelines in a place where nearly half the population lives below the poverty line.

A statue of a brown trout greets drivers entering Baldwin. The community is one of several across the U.S. navigating the expansion of immigration detention. (Photo by Alexa Durben/News21)

“There isn’t a lot of opportunities for individuals here,” Lake County Sheriff Rich Martin said. “If they want to have a job, they have to go elsewhere, usually, or they have to work at a lower-paying job.”

When The GEO Group this year opened the largest immigration detention center in the Midwest down the road, the town found itself caught up in a national conversation.

President Donald Trump’s administration has launched a massive expansion of immigration detention, a crucial step toward fulfilling Trump’s pledge to carry out mass deportations. The goal is to expand capacity to hold immigrants who, in the past, often would have been released while awaiting deportation.

Federal officials want to increase the number of beds from 41,500 to 100,000 nationwide by awarding billion-dollar contracts to private prison companies, primarily GEO and CoreCivic. Both companies’ stock prices surged by more than 60% after Trump’s reelection.

“We believe we have an unprecedented opportunity to assist the federal government in meeting its expanded immigration enforcement priorities,” GEO’s CEO, Dave Donahue, said on a May call with investors.

Lake County residents talk with employers at a hiring fair on Monday, June 23, 2025, in Baldwin. (Photo by Alexa Durben/News21)

The extensive tax and spending bill Trump signed in July gives U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement $45 billion – about five times its overall budget last year – to expand detention capacity.

“Our priority is to arrest and remove,” said John Tsoukaris, ICE field office director in Newark, New Jersey, where detention has prompted pushback and protests.

Across the U.S., some 60,000 people are being held in ICE detention — a 51% increase since January, according to the nonprofit Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

Despite Trump’s promises to target criminals, about 70% of those detained have no criminal record; many others have convictions for offenses as minor as a traffic violation.

As shuttered detention centers reopen, the communities that surround them are grappling with the consequences – questioning the morality of immigration detention, expressing concerns about shifting local identities and fighting back in the courtroom.

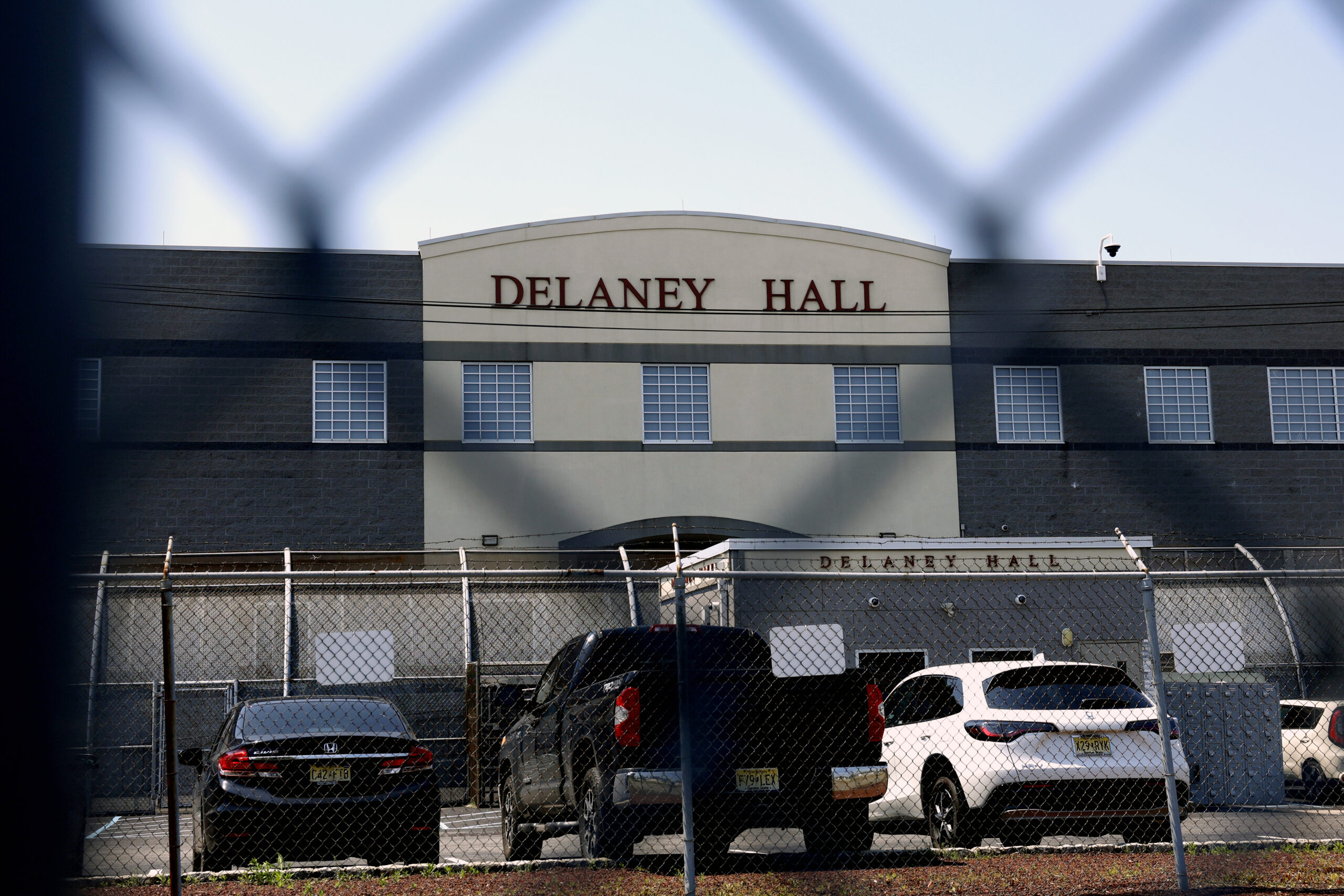

“We should be welcoming the stranger, not locking them up,” said Kathy O’Leary, who has led multiple demonstrations outside of Newark’s Delaney Hall, the first ICE detention center to reopen during Trump’s second term.

Mary Ortiz, a member of the Manistee Democratic Party, joins demonstrators on Saturday, June 21, 2025, in Baldwin. Some residents oppose the opening of an immigration detention center, while others hope it brings much-needed jobs. (Photo by Alexa Durben/News21)

Even Leavenworth, Kansas, a town synonymous with prisons, is hesitant to support detaining people outside the criminal justice system.

“We are known as a prison town,” local Ashley Hernandez said. “But having an ICE detention facility … is not something that many of the residents want.”

Up in Baldwin, the expansion of immigration detention brings skepticism, too.

But it also brings hope.

‘When you don’t have jobs, what do you do?’

The North Lake Correctional Facility has cycled through many phases since GEO opened it in 1999. It has housed juvenile offenders, out-of-state inmates and noncitizens convicted of federal crimes. It’s also closed four different times.

Each opening brought jobs, and each shutdown left Baldwin struggling.

“It’s just not consistent, you know?” Martin said. Never mind the politics, the Republican sheriff added. The community’s more immediate concern about the windfall from North Lake is that “it doesn’t last.”

After sitting idle for three years, the 1,800-bed facility reopened in June under a new ICE contract and a new name: the North Lake Processing Center. Situated off a dirt road 3 miles from town, the detention center could easily be missed. But its economic footprint is clear.

GEO estimates the center could generate over $70 million in its first full year of operations. When open, the facility is the largest employer in Lake County; even when idle, it remains the county’s biggest taxpayer.

The hope among those backing the reopening is that those economic benefits trickle down to their wallets.

Shelly Keene, executive director of Michigan Works! West Central, which matches job seekers with employers, said even short-term jobs in Baldwin would have an impact.

“Even if an individual is employed for a year or two making a high wage, it’s better than sitting at home and not making a wage at all, or maybe waiting tables or being a bartender,” said Keene, who added that two of her former co-workers had already returned to jobs at North Lake.

In June, Keene’s organization held a hiring fair in Baldwin to help fill 500 positions at the detention center. And although GEO employees reassured potential applicants that the facility was there to stay, advocacy group No Detention Centers in Michigan notes that GEO mostly hires outsiders, with just 69 of 300 jobs going to Lake County residents the last time the facility operated.

Keene acknowledged that many locals either don’t meet GEO’s qualifications or aren’t interested, leaving the company to look outside the county for employees.

Still, she said: “Having individuals traveling in and out of Lake County, they’re spending their money at the gas stations. They’re stopping at Jones’ for ice cream. They’re going to Barski’s for dinner.”

Facilities currently contracting with ICE and sites (red) already expanded or under consideration for expansion.

Those who oppose the facility argue that the promised economic benefits come at too high a cost.

In June, about 150 protesters gathered at a park near Baldwin, holding signs and chanting, “No to GEO! We can do better!” The demonstration, organized by the Democratic Party in next-door Manistee County and No Detention Centers in Michigan, focused on the morality of detention.

“It’s a carceral community that holds the town hostage, and then when they’re done, they leave,” organizer Eric Lampinen said.

Lampinen, who lives about 45 miles from Baldwin, said he doesn’t judge locals who support the facility.

“I get it,” he said. “When you don’t have jobs, what do you do?”

In an email to News21, a GEO spokesperson said: “We are proud of the role our company has played for 40 years to support the law enforcement mission of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement,” adding that GEO follows federal regulations that “set strict requirements on the treatment and services ICE detainees receive.”

Sara Maddox is a waitress at Shoey’s Log Bar – a “Baldwin staple for nearly 100 years!” as its Facebook page boasts. At the horseshoe-shaped bar, Maddox laughs with regulars and greets them by name.

She thinks most of the opposition to the new detention center is coming from outsiders. “The protests don’t exactly show the way that we feel here,” she said.

A few of her friends applied at North Lake, drawn by one of the area’s few jobs with strong benefits. At the same time, Maddox remembers how takeout orders dropped by almost 15% when North Lake closed in 2022.

“We’re excited for the growth, but I think the up and down of the North Lake facility, the opening and the closing, has taken its toll on the community,” she said.

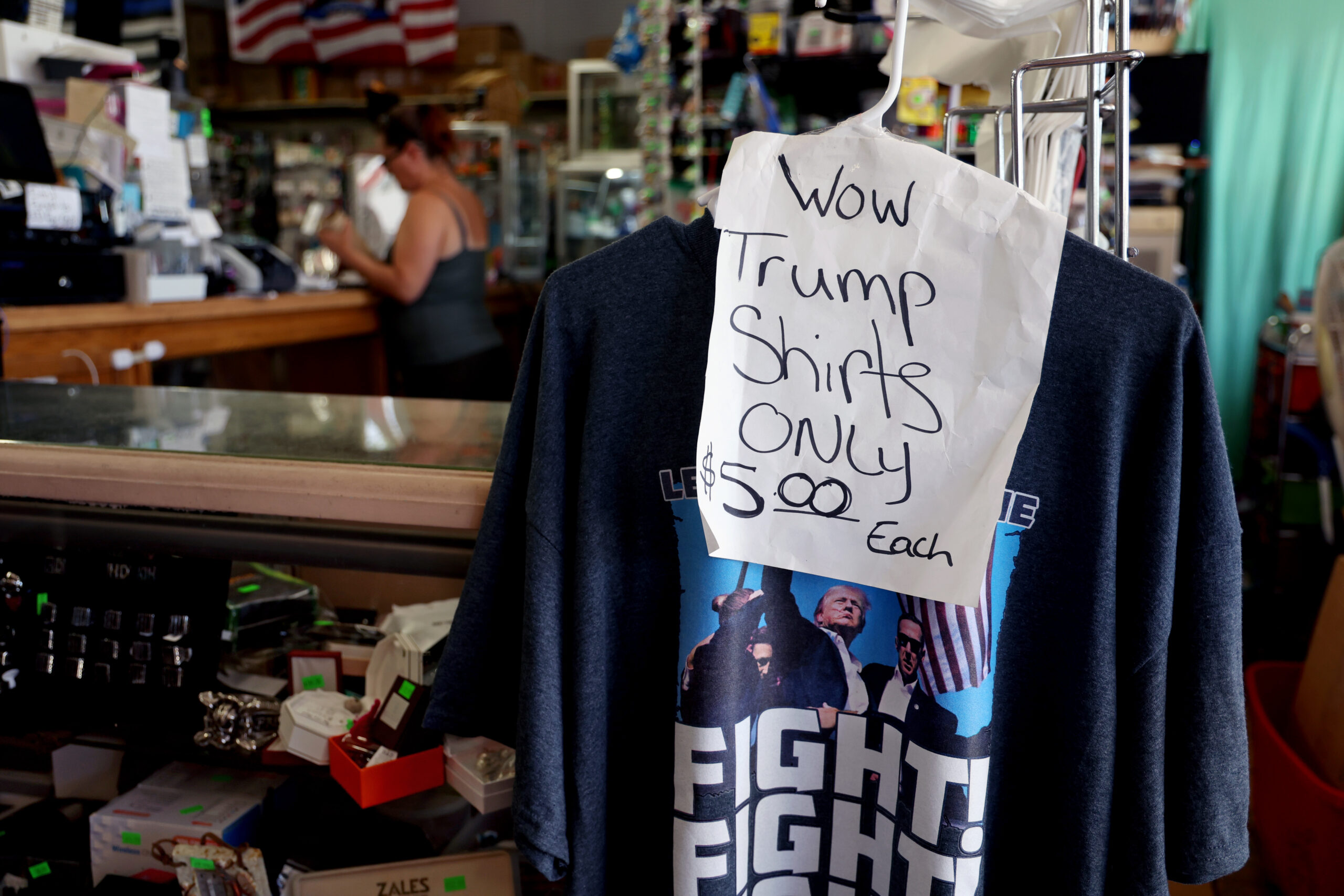

Lake County is Trump country. Some 65% of residents voted for him over Kamala Harris. For residents such as Debbie Russell, though, the detention debate isn’t about politics – it’s about the needs of her neighbors.

Russell has lived in Baldwin for more than 50 years and works at her daughter’s fabrics shop. While she does not fully agree with how the administration is handling immigration, she supports the reopening of North Lake.

“I just hope they stay open and it goes on for a while,” she said.

Left: An abandoned family diner turned “TrumpLand” sits on the side of a highway in Mason County, Mich. The next-door town of Baldwin is navigating the expansion of immigration detention. Center: Clothing in support of President Donald Trump hangs in Northern Treasures, a shop in Baldwin. Right: Merchandise lines a shelf in Northern Treasures. (Photos by Alexa Durben/News21)

Communities in at least eight states, some deep red, others the bluest of blue, are navigating the reopening of detention centers, several of which have histories of abuse.

At least four places — Newark, Leavenworth, New York City and Washington state — have challenged the expansion of immigration detention, in some cases by citing local ordinances. Leavenworth, for instance, is suing CoreCivic for trying to reopen a facility without obtaining a special use permit.

But nowhere is the opposition more fervent than in New Jersey – a state where one in four residents is an immigrant.

‘Families are disrupted and communities are harmed’

A flag waves next to the Statue of Liberty on Friday, June 13, 2025. As the Trump administration expands immigration detention on an unprecedented scale, communities are grappling with the consequences. (Photo by Marissa Lindemann/News21)

The Statue of Liberty welcomes ships from the Atlantic as they enter New York Harbor but turns her back on Newark, where immigration detention spreads in her shadow.

Just 5 miles behind her lies GEO-owned Delaney Hall and its razor wire fences. From its doorstep, petrochemical storage vats block the view to the Passaic River. Garbage trucks rumble past, headed for the state’s largest trash incinerator up the road. And if the wind blows just right, the faint smell of burning flesh lingers from a nearby animal fat rendering plant.

This area, northeast of Newark Liberty International Airport, is zoned specifically for heavy industry. No one is supposed to live here. Hotels, community centers and even animal shelters are prohibited. The only “residential” buildings allowed are Delaney Hall and the Essex County Correctional Facility.

Delaney, which operated as an ICE detention facility from 2011 to 2017, can hold about 1,000 people, dwarfing the only other immigration detention center in the state by 700 beds. GEO reopened it May 1, despite yearslong efforts in New Jersey to put a stop to immigration detention.

In 2021, lawmakers banned state, local and private entities from entering into or renewing contracts for immigration detention, and several facilities ceased operations. CoreCivic sued, and a judge ruled that while New Jersey may limit state and local entities, it cannot prohibit private companies from doing business with ICE.

The city of Newark has also challenged detention. In an April complaint, officials alleged Delaney Hall was a danger to staff and detainees because GEO wouldn’t allow the city to inspect the plumbing, electrical work or elevators. GEO called the lawsuit “politically motivated.” The case is still pending even as operations at Delaney persist.

In the first month and a half after the facility reopened, tensions boiled over twice. First came a scuffle that resulted in the arrest of Newark’s mayor and the indictment of a congresswoman – both Democrats – who were trying to inspect the facility. In the second, four men escaped amid a clash between guards and detainees who were upset over conditions.

“Any sort of detention environment is obviously not going to present with good conditions, but private detention facilities are worried about their bottom line – profits are really their goal,” said Molly Linhorst, a staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey.

GEO declined to respond directly to emailed questions, but said in a statement that its support services are monitored by ICE and other organizations within the Department of Homeland Security to “ensure strict compliance.”

The company said it provides services that include “around-the-clock access to medical care, in-person and virtual legal and family visitation, general and legal library access, translation services, dietician-approved meals, religious and specialty diets, recreational amenities, and opportunities to practice … religious beliefs.”

GEO referred questions to ICE; the agency’s national office did not respond to requests for comment.

Tsoukaris, the Newark ICE director, said he doesn’t understand why people are protesting facilities such as Delaney Hall.

“If you’re here illegally and you’re committing crimes, I don’t know why some people think it’s OK,” Tsoukaris said, despite statistics that show a majority of those detained have no significant criminal record. “You’re allowed to protest. But why are you protesting?”

Leaving the facility one morning in June, K.B., an American citizen who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of losing her nursing job, led her toddler son toward their car.

She had just finished visiting her husband of two years, who has been in the country for the past 21. Originally from Brazil, he was detained based on a 2005 deportation order, which a lawyer had been working to get dismissed, K.B. said.

Their situation reflects a new reality for immigrants without legal status. A year ago, ICE probably would have ignored someone like K.B.’s husband, who she said has no criminal record. If he had been detained, he likely would have been released pending resolution of the deportation order.

K.B. said her husband’s work as a general contractor accounted for the vast majority of their combined $120,000 income.

“We’d do everything like a family,” she said through tears. “Now, it’s totally changed. I’m starting to feel the burden of taking all of the responsibilities: taking care of the house, the bills, having to work and now having to find child care.”

Advocates worry K.B.’s story could become more common.

Said Linhorst of the ACLU: “The more detention beds we get, the more people are detained, which means the more families are disrupted and communities are harmed.”

A prison town’s identity is put to the test

Storefronts and a theater marquee line a street in downtown Leavenworth, Kan. Leavenworth is one of several cities embroiled in the debate over reopening or expanding immigration detention centers. (Photo by Alexa Durben/News21)

With its historical landmarks and Victorian homes flying U.S. flags, Leavenworth radiates small-town Americana.

As the first incorporated city of Kansas, the community carries multiple identities: a town rooted in military tradition and pioneer history, yet nationally known for the five prisons scattered around town.

“It’s the tenacity of the people that really defines Leavenworth,” said Ashley Hernandez, who works with the local Sisters of Charity. “Leavenworth is not made up of a bunch of people that are willing to just roll back and let something happen.”

Now, that identity is being put to the test.

CoreCivic is seeking to reopen the Leavenworth Detention Center under a contract with ICE to hold up to 1,000 people. The city has sued, leading to a temporary injunction blocking the facility from reopening without a permit.

Frustrated by the national attention, City Manager Scott Peterson said the city’s stance is not political, but simply a land use issue.

“There’s more to this town than just a fight with a CoreCivic facility – and more to this town than the prisons,” he said.

Left: Scott Peterson, city manager of Leavenworth, Kan., reviews a document at City Hall. Center: CoreCivic’s Midwest Regional Reception Center sits empty on Friday, May 30, 2025. Right: A mural recognizes Leavenworth as the first incorporated city in the state. (Photos by Alexa Durben/News21)

Yet prisons have long shaped the town’s narrative, economically and culturally.

After the Fort Leavenworth U.S. Army base and the Veterans Affairs hospital, prisons are Leavenworth’s third-largest employer. Home to the nation’s oldest federal penitentiary, the city of 37,000 has housed infamous figures such as Al Capone and Machine Gun Kelly.

CoreCivic’s ties to Leavenworth run deep. Its CEO, Damon Hininger, was born in the city and started his career as a corrections officer at the Leavenworth Detention Center, which opened in 1992 to house people awaiting trial on federal charges.

CoreCivic began talks with Leavenworth County officials about reopening the detention center during the Biden administration, but some residents pushed back over rumors that migrants would be processed and then released into town while they awaited court proceedings.

In its new proposal, CoreCivic promised that “no ICE detainees will be released into the Leavenworth community.”

The Leavenworth Detention Center — now rebranded as the Midwest Regional Reception Center — faced years of scrutiny. A 2017 Department of Justice report found it dangerously understaffed, with an officer vacancy rate as high as 23%.

Opposition has coalesced into a grassroots coalition of residents and immigration advocates who meet weekly in a grocery store Starbucks. They organize public panels, attend City Commission meetings and hold “teach-ins” to explore ways to “keep CoreCivic’s doors closed.”

At one recent panel, about 90 people gathered to protest the reopening, listening as former CoreCivic employees shared accounts of violence and neglect.

“The job is not worth it,” said attendee Muñeca Nieves, who volunteers with an immigrant advocacy organization. “They may pay well, but at what risk?”

Bill Rogers, a former CoreCivic guard, references his employee handbook during an interview on Saturday, May 31, 2025, in Leavenworth, Kan. Leavenworth is one of several cities embroiled in the debate over reopening or expanding immigration detention centers. (Photo by Alexa Durben/News21)

Joining the fight are the Catholic nuns at the Sisters of Charity, who have been speaking out at news conferences and holding prayer vigils.

“Our sisters have been moved, in a way that I haven’t seen them moved before, toward action,” said Rebecca Metz, who directs the social justice advocacy office for the Sisters of Charity in Leavenworth. “This has really set a fire in their sails, and they’re ready.”

In an emailed statement, CoreCivic acknowledged past challenges at its Leavenworth facility but objected to “broad and generalized criticisms of the conditions in which our facilities operate.”

“Our responsibility is to care for each person respectfully and humanely while they receive the legal due process that they are entitled to,” wrote company spokesman Ryan Gustin. “All our immigration facilities operate with a significant amount of oversight and accountability.”

Despite growing opposition, Leavenworth remains a town of contrasts, given that some residents support the reopening of the facility.

Jason Claire, who runs a military antiques and surplus shop, said he welcomes the expansion as an opportunity for a struggling downtown.

Claire said city officials are too focused on shaping Leavenworth’s image, rather than addressing its economic challenges. He pointed to recent efforts by leaders to rebrand Leavenworth as the “First City of Kansas,” a nod to its more charming pioneer roots.

“They’ve worked to keep it from being just a prison town,” Claire said. “But when you get down to soup and nuts, it’s a prison town.”

Attendees attend a panel discussion about immigration detention on Friday, May 30, 2025, in Lenexa, Kan. Leavenworth, about 35 miles north, is one of several cities embroiled in the debate over reopening or expanding immigration detention centers. (Photo by Alexa Durben/News21)

In 2024, 60% of Leavenworth County voted for Trump, and like some residents of Baldwin, Claire believes the most vocal opposition to detention comes from a politically motivated group of outsiders.

“They’re shooting themselves, and our community, in the foot, because it’s an opportunity to help spur the city and get it going,” Claire said.

Despite Claire’s stance, about 90% of the more than two dozen people who addressed the facility at City Commission meetings from February to June spoke against it, according to a News21 review of meeting minutes.

The legal battle continues, but for many, the fight is about more than proper permitting or economic opportunity.

The debate has exposed a deeper reckoning over the moral cost of immigration detention in America — and whether a town long defined by incarceration is willing to profit from another chapter of it.

“We’re taking away children’s parents,” said Sister Therese Bangert, a member of the Sisters of Charity. “We’re just causing anguish to lock them up. And then some people, like CoreCivic, are making money on it.”