Under Trump, ‘sanctuary’ cities, states come under fire over immigration policies

From left to right, Jessica Loomis, Louis Ramirez, Lizbeth Estrada and Reyes Estrada take the ferry to the Statue of Liberty. In July, the Trump administration sued New York City and its mayor, arguing the city’s sanctuary policies “impede the federal government’s ability” to enforce immigration laws. (Photo by Marissa Lindemann/News21)

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

CRETE, Neb. — In an unassuming town tucked amid corn fields and industrial plants, residents lounge in front of their homes during lunch breaks, music and laughter the only sounds to break the silence along two-lane streets.

This community of 7,000 people is 30 minutes southwest of the bustle of the state’s capital, and it has always considered itself a welcoming place. But Crete’s reputation for open arms came to the fore as the town’s Hispanic population increased fourfold over two decades.

In February, Crete became the first town in the state to join a network of 28 “Certified Welcoming” cities and counties, tangible proof that the town supports its new residents.

It’s a story common around the country as newcomers look to establish lives in the U.S. Some towns are shifting resources toward their growing immigrant communities. Like Crete, some have established themselves as “welcoming.”

But don’t call Crete a sanctuary city — because it’s not. It doesn’t want to be one, either.

“We just offer assistance to anybody and everybody,” said City Administrator Tom Ourada.

Left: A mural of historic downtown Crete, Neb., decorates the outside of a building. Crete became “Certified Welcoming” in February, reflecting the town’s efforts to welcome its immigrant community. Right: The Bunge food mill is one of three major industrial plants in Crete. Over the past three decades, industries like this helped lure more and more immigrants to move here. (Photos by Aaron Stigile/News21)

Under President Donald Trump’s second administration, “sanctuary” has never been more taboo – and being labeled as such could bring increased scrutiny or cuts in federal funding.

Trump’s immigration policies are targeting so-called sanctuary cities and states, but also hospitals, churches and schools, areas that were once off-limits to immigration agents.

“No more Sanctuary Cities!” Trump wrote in an April Truth Social post. “They protect the Criminals, not the Victims. They are disgracing our Country, and are being mocked all over the World.”

There’s no legal definition of “sanctuary,” but the term typically describes an area with laws limiting collaboration with federal immigration agencies. That often means local jails aren’t allowed to hold inmates for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Others are barred from sharing inmates’ immigration status with federal agents.

Advocates of sanctuary policies say collaboration between local police and federal immigration agents erodes trust with the community and leads immigrants to avoid reporting crimes for fear that it’ll affect their status. Several studies on the subject confirm that.

Nevertheless, pressure to denounce sanctuary has mounted since Trump took office. Some jurisdictions are rejecting the sanctuary label and vowing to do their part in accomplishing the president’s crackdown on immigration.

New Hampshire this year passed two laws banning sanctuary cities, and Utah passed a law making it easier for immigrants with misdemeanors to be deported. Florida and Texas required most county sheriffs to enter agreements to increase collaborations with ICE.

Even the Democratic mayor of Washington, D.C., proposed repealing that city’s sanctuary law; a bill is pending in Congress that would do so.

Meanwhile, jurisdictions that embrace sanctuary policies are facing political consequences.

Crete City Administrator Tom Ourada oversees the day-to-day functioning of the town. He wholeheartedly believes that Crete’s “secret weapon” to success is its immigrant community. “People move here, and they don’t want to move away.” (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

In July, the Trump administration sued New York City and its mayor, arguing the city’s sanctuary policies “impede the federal government’s ability” to enforce immigration laws.

Republicans in the U.S. House have grilled the mayors of Boston, New York, Chicago and Denver – and the governors of Minnesota, Illinois and New York – over their sanctuary policies.

“It’s absolutely sickening that sanctuary jurisdictions seek to protect these criminals rather than protect Americans,” U.S. Rep. James Comer of Kentucky said during a June committee hearing.

At Trump’s request, the Department of Homeland Security in May published a list of hundreds of cities, counties and states that it determined were sanctuaries.

The list included states with laws limiting cooperation with ICE, like California and Illinois, but also such cities as Nashville, Tennessee, and Boise, Idaho, where state laws prohibit sanctuary policies.

Huntington Beach, California, a Trump stronghold, appeared on the list despite declaring itself a “non-sanctuary city” and filing a lawsuit in January against California’s sanctuary law.

DHS removed the list from its website just days after it went up.

Crete wasn’t on the list. But under heightened political pressure, small towns like it are forced to decide what it means to support their immigrant residents without uttering the one prohibited word.

A town of immigrants – then and now

Left: A “Welcome” banner hangs on a lamppost in Crete. Right: Several stores along Crete’s Main Avenue are run by immigrants and have Spanish names. “When we came, it wasn’t much Latinos,” said Arminda Avelar, who works at the Super Latina Market. “But it was the possibility that you can really grow here.” (Photos by Aaron Stigile/News21)

Long before becoming “Certified Welcoming,” residents of Crete considered their town welcoming with a lowercase “w.” It’s the type of place where strangers smile as they pass on the sidewalk, and driving from one side of the town to the other takes no more than 10 minutes.

Crete has always been a town of immigrants. Czech nationals were among the earliest residents in the mid-1800s, along with settlers from Germany and the Eastern U.S.

That’s what made the town so welcoming to Hispanic immigrants, said Janet Jeffries, a historian and president of the Crete Heritage Society. Her Czech ancestors arrived in Nebraska four generations ago.

“We are quite an accepting group here, because a lot of us grew up with this immigrant history of our own,” she said.

Central and South American immigrants started moving to Crete in the late 1990s, drawn by work at the meatpacking facility on the edge of town. That plant is now owned by Smithfield Foods.

The Smithfield meatpacking facility, located on Crete’s outskirts, employs nearly 2,000 people. Crete’s immigrant community has grown since the 1990s, when people moved to town to work at the plant. (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

As Hispanic residents started families and recommended Crete to their relatives, the town’s Spanish-speaking population grew. Today, almost half its residents identify as Hispanic or Latino – and Crete has evolved.

In 2016, the town launched a Community Assistance Office to help residents with housing, education and immigration services. Churches recruited Spanish-speaking pastors to lead Spanish-language services. Today, the lone movie theater shows films in Spanish and English.

Jennifer Cardoso Franco, 21, has always felt welcome in Crete, where she was born and raised. She and five of her siblings, along with her mother and stepfather, live in a three-bedroom house a few minutes from Main Avenue.

Immigration issues are at the top of Cardoso’s mind. She is a U.S. citizen, but her family members have mixed immigration statuses.

Her father, who lives out of state, doesn’t have legal authorization to be in the country. Her uncle was recently deported to Mexico; he wears a cross around his neck in a family photo that hangs above the living room couch.

On a Wednesday afternoon, Cardoso’s mother, America Franco Adame, lays dozens of beaded necklaces in a colorful array on the kitchen table. The family sells jewelry from Mexico and wholesale clothes, hair products and toys out of the garage for extra income.

Franco has worked at the meatpacking plant on and off since 2007 under a work permit, but that authorization expired in June. She said she has filed petitions for permanent residency for about 20 years – but none has been successful.

“It’s hard to be legal in this country,” she said.

Her daughter, a political science student in her final year of college, has tried to help by working with lawyers to gather documents and file paperwork. She hopes to work in immigration law herself one day.

Cardoso knows Crete as a friendly town where “the community always comes together” for events and celebrations. She said some people exhibit racist attitudes, but that’s “just kind of inevitable.”

In one high-profile case last year, a white man shot seven Guatemalan neighbors, then killed himself. The shooter once told the victims to “speak English” and go back to where they came from, according to police.

The town’s welcoming attitude doesn’t allay worries about immigration enforcement, either.

In June, immigration agents arrested 76 people at a meatpacking facility in Omaha, 80 miles away. It was the largest workplace raid in Nebraska this year.

That same month, ICE came looking for two Crete residents and arrested one, according to Ourada, the city administrator.

“There’s immigrants everywhere,” Cardoso said. “You just don’t know whose house they might target next.”

When Ourada first approached the mayor and City Council about becoming a “Certified Welcoming” city, he said they worried that “welcoming” would be misinterpreted as “sanctuary” – and the latter could come with consequences.

In April, Trump issued an executive order threatening to revoke federal funds from sanctuary jurisdictions. He issued a similar warning during his first term, but legal challenges prevented funding from being pulled.

About 38% of Nebraska’s state budget came from federal grants and contracts last year. In Crete, federal funds help with economic development, Ourada said.

Michael Kagan, a professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who has written about sanctuary cities, said Trump’s increased pressure on cities and states to comply with federal immigration policies could have the desired effect.

“When the Trump administration is more aggressive and seeming to menace anyone who might not do what it wants, some local governments might roll over more quickly now because of that aggression,” he said.

‘Sanctuary city lite’

The Rev. Christopher Stoley celebrates a Spanish-language Mass in Crete. Stoley has been with his church for eight years. “The best part is being able to be in people’s lives,” he said. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

Draped in white and gold robes, the Rev. Christopher Stoley presses his palms together and looks out at the parishioners who’ve gathered after work for Friday Mass.

Since the 1890s, Catholics in Crete have worshipped in the same 130-year-old church, a grand building lined with stained-glass windows. Back then, the congregation largely spoke Czech or English.

Now, the priest bows his head and says, “Oremos.” Let us pray.

Stoley was assigned to Crete’s Sacred Heart Catholic Church in 2015. Today, he estimates that 80% of his parishioners are Hispanic or Latino – and he can see how anxious they are about immigration enforcement.

Stoley has noticed a few parishioners staying home, concerned that leaving the house could put them at risk of being stopped and detained. Worries are heightened by community groups on Facebook, he said, where rumors of ICE raids are common and often unfounded.

“Everyone’s so worried and kind of panicking,” he said. “We try and give them as much as we can to alleviate some of that pressure.”

Left: The central building at Sacred Heart Catholic Church was built in the 1890s, when many of Crete’s residents were Czech immigrants. (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21) Right: Parishioners gather for a Spanish-language Mass at Sacred Heart Catholic Church. The parish serves some 750 families; about 80% are Hispanic. “It doesn’t matter if they’re white, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Catholic, not Catholic. If they need something, that’s why we’re here,” the Rev. Christopher Stoley said. (Photo by Alissa Gary/News21)

Outside of Mass, Stoley dons the all-black clothing and white collar of an off-duty priest. He cracks jokes with kids at the church’s summer camp as he enters his office, where a copy of the Catholic catechism, written in Spanish, sits on his desk, along with a painting of Jesus holding a red heart – gifted to him by a parishioner who brought it back from El Salvador.

Historically, along with schools and hospitals, churches were considered “sensitive locations” where ICE had minimal access. After the Trump administration revoked that precedent, Stoley came up with a plan of action.

If agents come to the church, he’ll ask to see a warrant. If they have one, he said, “Our hands are kind of tied, unfortunately.” If they don’t, he’ll turn officers away.

Stoley said he shared that protocol with his congregation, embedded in a reading about trust.

To Stoley, Crete is like a “sanctuary city lite” — a town with welcoming policies, but one that lacks the major protections afforded by the sanctuary designation. The town might be better off with the latter, he said.

“But as a welcoming city, I think we’ll be OK that way, too.”

The Rev. Christopher Stoley looks at a skylight in St. James Catholic School. Though Crete isn’t a sanctuary city, Stoley said the town’s welcoming efforts make it a “sanctuary city lite.” (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

The safety debate

Safety is at the heart of the wrangling over sanctuary.

Opponents of sanctuary policies argue they endanger cities by letting “criminals” walk free, rather than be detained by ICE. Nationally, police departments and sheriff’s offices are partnering with ICE via its 287(g) program, which trains local officers to act as immigration agents with a goal of increasing arrests.

“If you’re a sanctuary city, you’re not doing the right thing for your citizens,” U.S. Sen. Rick Scott, a Florida Republican, said in an interview with Fox News. “I don’t think anybody in this country wants criminals or somebody selling drugs to their kids in their cities.”

However, research shows that sanctuary status doesn’t cause higher crime, said Charis Kubrin, a professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California, Irvine, who has extensively studied the effect of immigration on crime and written a book on the issue.

The key takeaway, she said, “is that immigrants actually have lower involvement than the native-born on an array of crime measures. That includes overall offending, violent crime, property crime, drinking and driving, school violations, you name it.”

For one study, Kubrin specifically examined California’s 2017 sanctuary law and found it had no effect on the amount of violent and property crime in the state.

What has been documented, she said, is a decrease in trust between residents and law enforcement in places where police collaborate with ICE.

“That can hinder people from reporting victimizations, reporting that they’ve seen crimes, serving as witnesses,” she said. “It minimizes trust, and it makes people concerned. That, in fact, will harm public safety.”

Officials in cities that have 287(g) agreements disagree with that assessment. In an interview with News21, Sheriff Gordon Smith of Bradford County, Florida, said any assertion that the program affects trust is “hogwash” and “political banter.”

Crete police aren’t a part of that program, Ourada said, but if ICE asks for help enforcing warrants, the town’s officers are required by law to comply. That type of assistance, he added, fundamentally distinguishes Crete from a sanctuary city.

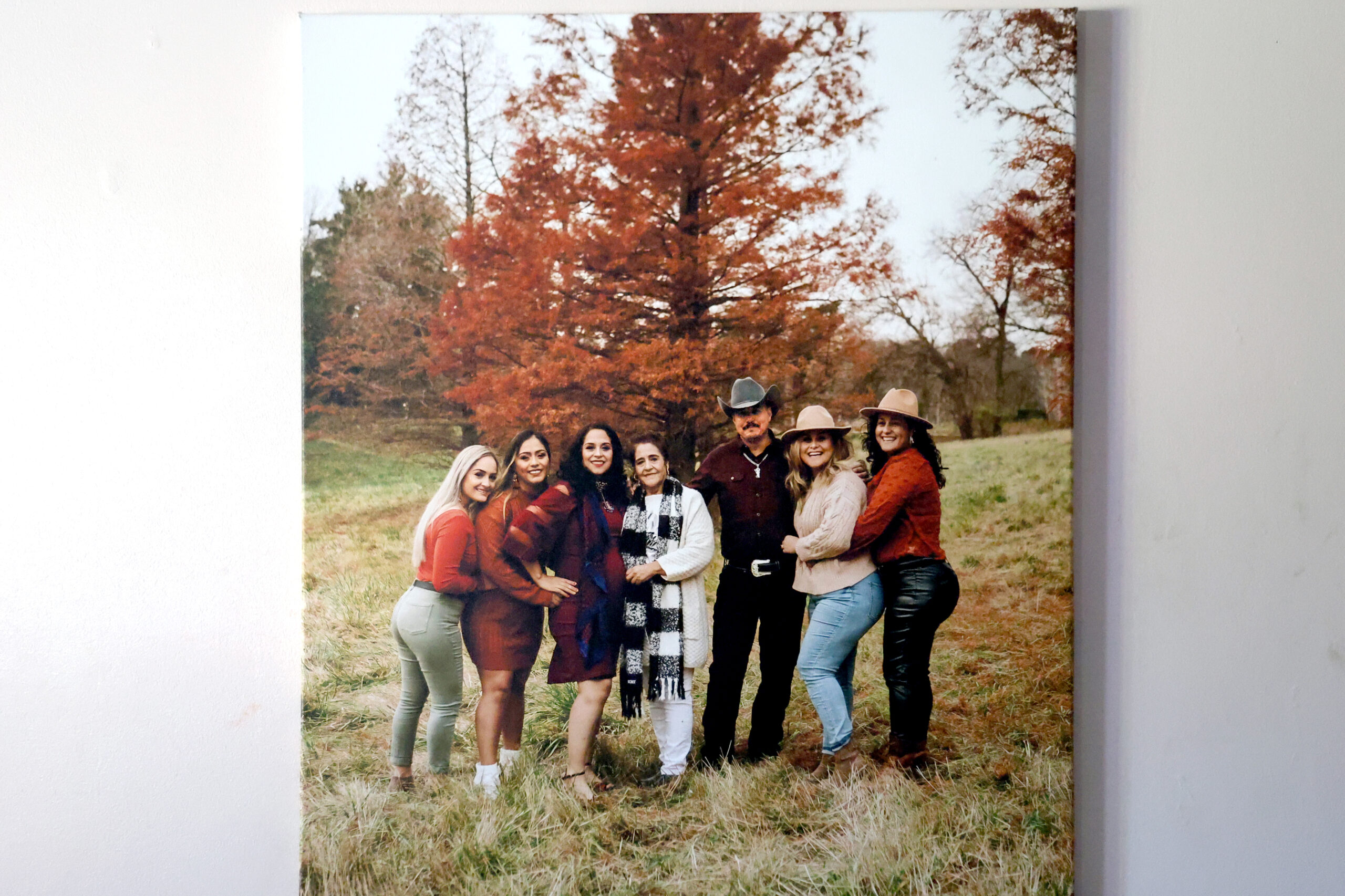

Left: Carely Adame Ortiz, a Crete resident, said that when the town became “Certified Welcoming,” it was a “very big deal.” “It just shows the community we are. It represents us.” Right: A photo of Carely Adame Ortiz and her family hangs on the wall in her living room in Crete. Adame Ortiz’s parents emigrated from Mexico to Crete before she was born. (Photos by Aaron Stigile/News21)

Though police are obligated to work with ICE, Crete resident Carely Adame Ortiz said she trusts how officers will go about that. Adame Ortiz’s parents emigrated from Mexico before she was born, and both now have legal status.

“They’re just doing their job,” Adame Ortiz said of the town’s police. “And you can’t really not do your job.”

The city wants the relationship between police and residents to remain strong, Ourada said, adding that the Police Department works with the Community Assistance Office to build trust with residents. He pointed to a class that officers assisted with to help new arrivals earn their

driver’s licenses.

“When ICE leaves, the police will be going back to giving warnings for speeding, and helping … with driving classes, and chasing after barking dogs, and telling people, ‘You can’t park there,’ and that kind of thing,” Ourada said, “because that’s what we do.”

‘Enable belonging for everyone’

For town leaders, being “welcoming” is a perpetual task. “It isn’t hard,” Ourada said, “but it takes work.”

The Community Assistance Office develops “welcoming” resources, such as helping students apply for financial aid and collaborating with an immigrant advocacy group to hold know-your-rights presentations.

Since it opened in 2016, the office’s goal has been to support Crete’s residents however it can, said Marilyn Schacht, community assistance director since 2023.

Schacht was born in Guerrero, Mexico, and arrived in the Crete area in the late 1990s, when her parents pursued jobs at the meatpacking facility. She didn’t have legal status for much of her life and struggled with the immigration system, an experience she said allows her to “walk alongside” newcomers as they gain their footing.

“It’s kind of full circle for me now to help implement some of the initiatives or policies that also helped my parents be successful,” Schacht said.

Marilyn Schacht, director of Crete’s Community Assistance Office, sits in her office with her husband, Ryan, an immigration services officer. Schacht emigrated as a child from Mexico with her family. (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

She helmed the city’s push to become “Certified Welcoming,” a certificate awarded through the national nonprofit Welcoming America. The organization, founded in 2009 by the former director of a Tennessee immigrant rights group, aims to “enable belonging for everyone, and explicitly immigrants,” its website says.

To become certified, cities must demonstrate that all residents, immigrants included, can equally participate in civic life, education and social services.

After about a year of applications and paperwork – including a 13-page audit of its welcoming efforts – Crete earned the designation in February.

The certificate helped Schacht connect with other welcoming cities – places such as Dayton, Ohio, and Louisville, Kentucky – and consider how Crete could improve, she said. But it also reflected much of the work the town already was doing to welcome immigrants.

“It’s just the way their community operates,” said Christa Yoakum, a county commissioner in Lincoln who works on immigration advocacy with the organization Nebraska Appleseed. “People feel like they belong.”

In Ourada’s City Hall office, a sprawling map of the town hangs just above his desk.

Crete City Administrator Tom Ourada talks about the city’s efforts to become “Certified Welcoming.” “We are the quintessential melting pot,” he said. (Photo by Aaron Stigile/News21)

He’s held this job for 12 years now, charged with ensuring the town – and its people – thrive. And he wholeheartedly believes that Crete’s “secret weapon” to success is its immigrant community.

“I won’t say we’re one big, happy family – we have trials and tribulations, like anybody does,” Ourada said. “But people move here, and they don’t want to move away.”

News21 reporter Aaron Stigile contributed to this story.