Lives in limbo: Amid Trump immigration actions, DACA holders navigate the unknown

A.L.E. holds a photo of her and her parents taken in Mexico shortly before the family moved to the U.S. A DACA holder for seven years, the 24-year-old is one of over 500,000 current recipients in limbo as they wait to see what President Donald Trump does with the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/ News21)

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

FORT WORTH, Texas – On Christmas Day her junior year of high school, A.L.E. sat near the tree, ready to open gifts. When her mom handed her a box, telling her it was a “big present,” the then-16-year-old expected a new pair of shoes.

Instead, she found an envelope. Inside was her Employment Authorization Document card, confirming she had been approved for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program.

Seven years later, A.L.E. holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of North Texas, works at a law firm as a paralegal, and hopes to go back to school to study immigration and constitutional law.

Yet she still has no permanent legal status to remain in the United States.

“I have dreams. I want to be able to work,” said the 24-year-old, who asked not to be identified with her full name because she worries any publicity could affect her chance of one day obtaining legal status.

“This was supposed to be temporary,” she added of the DACA program. “But it’s just an ongoing cycle where every two years you have to renew, you have to pay the fee, you have to make sure that you don’t get in trouble – you don’t get a parking ticket – in case something comes up and they’re like, ‘No.’”

DACA turned 13 in June. The Obama-era program, which allows those brought into the U.S. illegally as children to stay and work, was never meant to be more than a stopgap on the pathway to conditional permanent residence, and ultimately citizenship, for those known as Dreamers.

Since 2012, about 835,000 people have been protected by DACA. But the program, along with the 525,000 immigrants who are still part of it, remains in limbo as the Trump administration implements a sweeping immigration agenda that includes workplace raids, increased detention and deportations of thousands of others.

The largest segment of active DACA recipients – 426,570 – were born in Mexico, but DACA holders hail from 160 different countries and territories, and more than 23,000 are from countries outside of Latin America – places such as South Korea, the Philippines and Jamaica.

Teenage beneficiaries are now adults with careers, homes, spouses and children. Today, the average age of a DACA holder is 31, according to federal data, and almost a third of active recipients are married. Some 88% of the initial DACA recipients from 2012 are in the labor force, according to the advocacy organization FWD.us, and 49% of those recipients have at least some college education.

“DACA recipients are part of the fabric of our communities and American in every way but on paper,” said Anabel Mendoza, communications director for United We Dream, which advocates for immigrant youths.

“I’ve met nurses; I’ve met doctors, students,” said U.S. Rep. Sylvia Garcia, a Texas Democrat sponsoring legislation to provide a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers. “They’re everywhere, and we will lose them – and lose that talent – if we don’t get the DREAM Act done.”

Yet another bill introduced in July by U.S. Rep. Maria Elvira Salazar, a Florida Republican, and Rep. Veronica Escobar, a Texas Democrat, would provide a pathway to lawful permanent residency for immigrants brought to the country illegally as children. “The Dignity Act,” which includes other, sweeping immigration reforms, remains in committee.

Since 2001, lawmakers have introduced at least 20 versions of the “DREAM Act” to provide Dreamers with conditional permanent residency, which they could use to meet naturalization requirements. None has passed, and Garcia’s bill has received no committee hearing or vote since it was introduced in February.

“I’m waiting, and I’ll wait patiently,” Garcia said, “because it’s about getting it done (for) these Dreamers who’ve been here – no other country but this one in their heart, their soul, in their mind.”

In 2017, during his first term, President Donald Trump tried to terminate DACA, arguing the move to establish the program circumvented immigration laws and was unconstitutional. However, the U.S. Supreme Court blocked that action.

Before taking office again, Trump said in an interview with NBC’s “Meet the Press” that he would work with Democrats on a plan for Dreamers, acknowledging that “some of them are no longer young people, and in many cases, they’ve become successful.”

Since then, though, Trump has provided few specifics about his stance or plans for DACA, but his administration has taken steps to curtail protections for Dreamers.

Protesters gather at the anti-Trump “No Kings Day” demonstration on Saturday, June 14, 2025, in downtown Los Angeles. (Photo by Sydney Lovan/News21)

In late August, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reversed a 2024 policy that made DACA recipients eligible for medical insurance under the Affordable Care Act; some 11,000 people are expected to lose coverage. Already, because of a court challenge, DACA recipients in 19 states had been prohibited from enrolling in the health program.

Trump also issued an executive order challenging laws that allow in-state tuition for college students who are in the country illegally. The U.S. Department of Justice has since sued to end such policies in several states, including Kentucky, Minnesota and Texas. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton quickly agreed to stop the practice, calling it “unconstitutional and un-American,” but Texas DACA holders are not affected because they are considered “lawfully present” in the U.S.

Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said immigration advocates and lawyers don’t know whether Trump will try to end DACA, given that officials have “not indicated whether they will do that, and they’ve not taken steps to do that.

“That’s the wild card,” he said.

Despite the protections DACA should offer, some recipients worry about being swept up in the administration’s mass deportation efforts.

In March, federal agents detained and immediately deported DACA holder Evenezer Cortez Martinez of Roeland Park, Kansas, after he returned from a visit to Mexico due to his grandfather’s death.

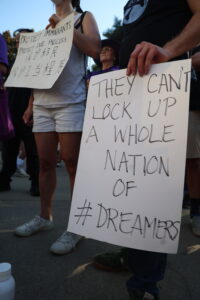

A protester at a demonstration on June 9, 2025, in Sacramento, Calif., holds a sign in support of those known as Dreamers, individuals who were brought to the U.S. illegally when they were children. (Photo by Sydney Lovan/News21)

Cortez Martinez’s DACA was valid through 2026, and he’d been granted advance parole – permission to travel abroad and then return to the U.S. But agents deported him anyway, citing a 2024 removal order that Cortez Martinez said he was not aware of.

The father of three eventually was allowed to return to the U.S. And although there have been few reported cases of people with DACA or advance parole being detained, Cortez Martinez’s lawyer, Rekha Sharma-Crawford, said she advises DACA recipients not to travel out of the country, even if they have legal permission to do so.

The “breakneck speed at which the policies are changing” is causing too much uncertainty, she said. “It’s just not safe for anyone right now.”

Legal challenges spanning more than a decade have also left Dreamers on unsteady ground. Some rulings favored DACA, such as when courts in 2015 dismissed a lawsuit by Mississippi to stop the program and in 2016 blocked Arizona from denying driver’s licenses to recipients.

Other rulings have diminished the program; those included a 2016 U.S. Supreme Court decision that effectively barred the Obama administration from expanding DACA.

More notably, based on another court decision, the government in 2021 stopped processing first-time applicants. While current recipients can still renew, FWD.us estimates some 500,000 people are eligible for DACA but can’t have their applications processed.

“It’s sad how we’re 13 years later, and we’re still going through the same process,” said a 26-year-old San Antonio resident who has twice tried – and failed – to get DACA. “I mean, by this time, we all deserve a pathway to citizenship.”

And while most states allow recipients to enroll in college and obtain in-state tuition, South Carolina, Alabama and Georgia restrict in-state tuition for DACA students at public universities, according to a data portal run by the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration.

“DACA recipients for … more than 10 years now have been on a constant roller coaster of lawsuits and litigation,” Sharma-Crawford said. “I think they completely understand the fragile ground that they’re on and that DACA can be taken away from them at any point.”

The DACA program remains in limbo even as the Trump administration implements other immigration proposals. Texas is home to nearly 88,000 DACA holders. (Photo by Mia Hilkowitz/News21)

The program has faced further setbacks in Texas, home to nearly 88,000 active DACA recipients – second only to California’s 147,000.

In January, a federal court ruled that part of the DACA program is unlawful but limited its finding to Texas, which argued that providing emergency medical services, social services and public education to recipients had cost the state more than $750 million.

Texas DACA holders are still protected from deportation, but the decision opened the door for the state to end work authorization. A district court judge will decide how the ruling should be implemented.

While other states could follow Texas’ lead and try to prove they’ve been harmed financially because of the program, Saenz said they are unlikely to do so.

“Texas was at great pains to show any injury from DACA – and we don’t think they succeeded at it – so other states will see it as arduous and resource draining,” he said in an email.

Advocates nevertheless worry that Texas could become the blueprint for how to take down DACA once and for all – piece by piece, state by state.

“They’re trying to chip away at the program … and that, I think, may be how they’re trying to go about dismantling the program,” said A.M., a 24-year-old DACA holder who lives near Houston. He asked to remain anonymous out of concern that he could lose his status or otherwise be targeted.

The American Immigration Council, an immigration advocacy group, estimates DACA recipients pay more than $5 billion in federal taxes and $3 billion in state and local taxes each year.

In Texas alone, the group reports, DACA-eligible residents contribute $2 billion in taxes and $6.2 billion in spending power – money that could be lost if recipients can’t work.

“That’s what is at stake here,” said Juan Carlos Cerda, a DACA recipient who serves as Texas state director for the American Business Immigration Coalition. “It’s jobs, and it’s the economic contributions.”

Some Dreamers and advocates worry Texas could become the blueprint for how to chip away at DACA in other states. “It’s a very scary moment right now for the program,” a 24-year-old recipient from Houston said. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

Many Texas recipients are weighing whether to move out of state so they can keep working, Cerda said, adding that he has heard from concerned employers as well.

“Employers have been coming to private discussions to discuss options to take and how to get engaged, and the solution here is for Congress to take action,” he said. “It’s an executive order, and it needs to become law.”

Nneka Achapu, founder of the nonpartisan African Public Affairs Committee, said she has little faith that Congress will pass anything to protect DACA recipients.

“While we love the idea of being able to change the status of many of the people who have been living here, we’re also realistic,” she said.

Only one Republican, U.S. Rep. Maria Elvira Salazar of Florida, has signed on as a cosponsor of the 2025 DREAM Act. News21 reached out to Salazar by phone and email but received no reply. Garcia said she’s reached out to other Republicans in the House to elicit support but doesn’t think many will sign on unless Trump backs the bill.

“This is just a dress rehearsal for when I can get it done,” she said, “when Democrats take the gavel back.”

Gaby Pacheco, president and CEO of TheDream.US – which provides college scholarships to students in the country without legal permission – said she and other advocates are trying to convey to lawmakers that it shouldn’t matter which political party is in control.

Either way, she said, Dreamers need relief.

“If Donald Trump was to happen to be the one that signs the DREAM Act … I’ll be the first one standing behind him, applauding the fact that it got done,” she said. “At this point, politics shouldn’t matter.”

News21 traveled to Fort Worth, San Antonio and the Houston area to speak with several Dreamers trying to navigate their lives and determine their futures, even as they wait to see what comes next. Three of the four asked to remain anonymous, fearful they – or their family members in the country illegally – could be targeted if they spoke out.

A businessman fights to stay for his family and workers

Zak Galindo poses for a portrait at his barbershop in Conroe, Texas. The 38-year-old credits his ability to obtain DACA with setting him on the path to becoming a successful business owner. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

Inside a barbershop nestled along a strip of woods in Conroe, Texas, Zak Galindo is starting his day.

The 38-year-old owns two barbershops, a coffee shop, and a bakery and deli. Across the four businesses, he employs 70 people with help from his wife, Sophie, who moved to the U.S. from England as a girl.

She, though, is a naturalized U.S. citizen. He is not, and DACA – to date – remains his only protection from deportation.

“If I was to get deported, it would affect a lot of people — it wouldn’t just affect me and my family,” he said. “It would affect everybody that’s within the business, and their families.”

Galindo obtained DACA before graduating from college. He and his wife now own four businesses. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

Galindo was 8 when his mother brought him and his two older sisters to the U.S. from Honduras in 1996. They settled in Chicago, where Galindo found community in the neighborhood barbershop. Eventually, the family moved to Texas to be closer to Galindo’s eldest sister.

At 17, Galindo obtained his license to be a barber, one of the few jobs in Texas that did not have a residency requirement. The job provided him with financial stability and helped him decide to pursue a degree in business at Sam Houston State University.

“I don’t know that I would have been able to even go through college or pay for college had I not had that profession, because I couldn’t have gotten another job,” he said.

Before graduating from college, he decided to apply for DACA – taking every precaution to ensure he remained eligible, including paying a friend to drive him back and forth to school because he couldn’t get a driver’s license.

DACA is open only to those who arrived in the U.S. before they were 16, have lived in the country since 2007 and were under 31 when the program started in 2012. Applicants can’t have been convicted of a felony or significant misdemeanor, and they must either be current students, have graduated from high school or have served in the military.

“It’s people that don’t cause any trouble, went to school,” Galindo said. “They’re good people. And if you meet a lot of them, they’ve gone on to be successful and to make a positive impact in their community and their jobs.”

Left: Galindo owns two barbershops, a bakery and deli, and a coffee shop. Right: Galindo and an employee discuss the schedule at Galindo’s Barbershop on Tuesday, June 17, 2025. Galindo is working to become a naturalized citizen amid the uncertainty surrounding the future of DACA. (Photos by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

Galindo was approved for DACA the same day he started an internship at an accounting firm, which would eventually lead to a full-time offer. After three years, he left to start his own barbershop.

Today, he’s one of those DACA success stories. He works closely with the Montgomery County Hispanic Chamber to advocate for other DACA recipients and shares his story publicly to help people understand, “This is what a DACA recipient looks like.”

“I wouldn’t have what I have now, wouldn’t be where I am now, if it wasn’t for DACA,” he said. “I feel like I’ve been blessed.”

Galindo has applied to become a naturalized citizen – like his wife of three and a half years. But the uncertainty of not having permanent status has forced the couple, who have been together for more than 10 years, to put off their dreams of starting a family.

“I still have DACA through the end of the year, but nothing’s guaranteed – and so hopefully everything goes as planned, and then we can start having some babies next year,” Galindo said. “We’re just kind of sitting in limbo in the meantime.”

He still holds out hope that lawmakers will act to allow Dreamers to permanently remain in the U.S.

“It doesn’t have to be full citizenship, because I also don’t think that we should cut the line,” he said. “But something to where we don’t have to fear, ‘Hey, DACA is over now,’ and we don’t have anything.”

A young Dreamer finds his voice

A.M., 24, covers his face for a portrait in Humble, Texas. A.M. became a DACA recipient when he was 15. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

For A.M., a 24-year-old living near Houston who obtained DACA when he was 15, growing up in Texas without legal status has always been “scary,” regardless of who was in the White House.

“There’s always been that constant fear … that at any moment you could be detained and deported,” he said.

Throughout elementary and high school, he said, he felt like he was “hiding in the shadows.”

He was just 5 or 6 when his parents explained what it meant to be “undocumented” and what he needed to do if he one day wanted to get papers: Behave well, and avoid trouble at all costs.

Classmates, who didn’t know why he followed rules to a T, made fun of him. When friends asked where he was from, he lied – claiming Houston as his hometown, rather than admitting his family moved from Tamaulipas, Mexico, when he was 3.

“I always had this idea that I had to do very good in school and I had to be very careful with what I did, because if I did one tiny little thing out of line, that was the end of it – and that was putting me and my family at risk,” he said.

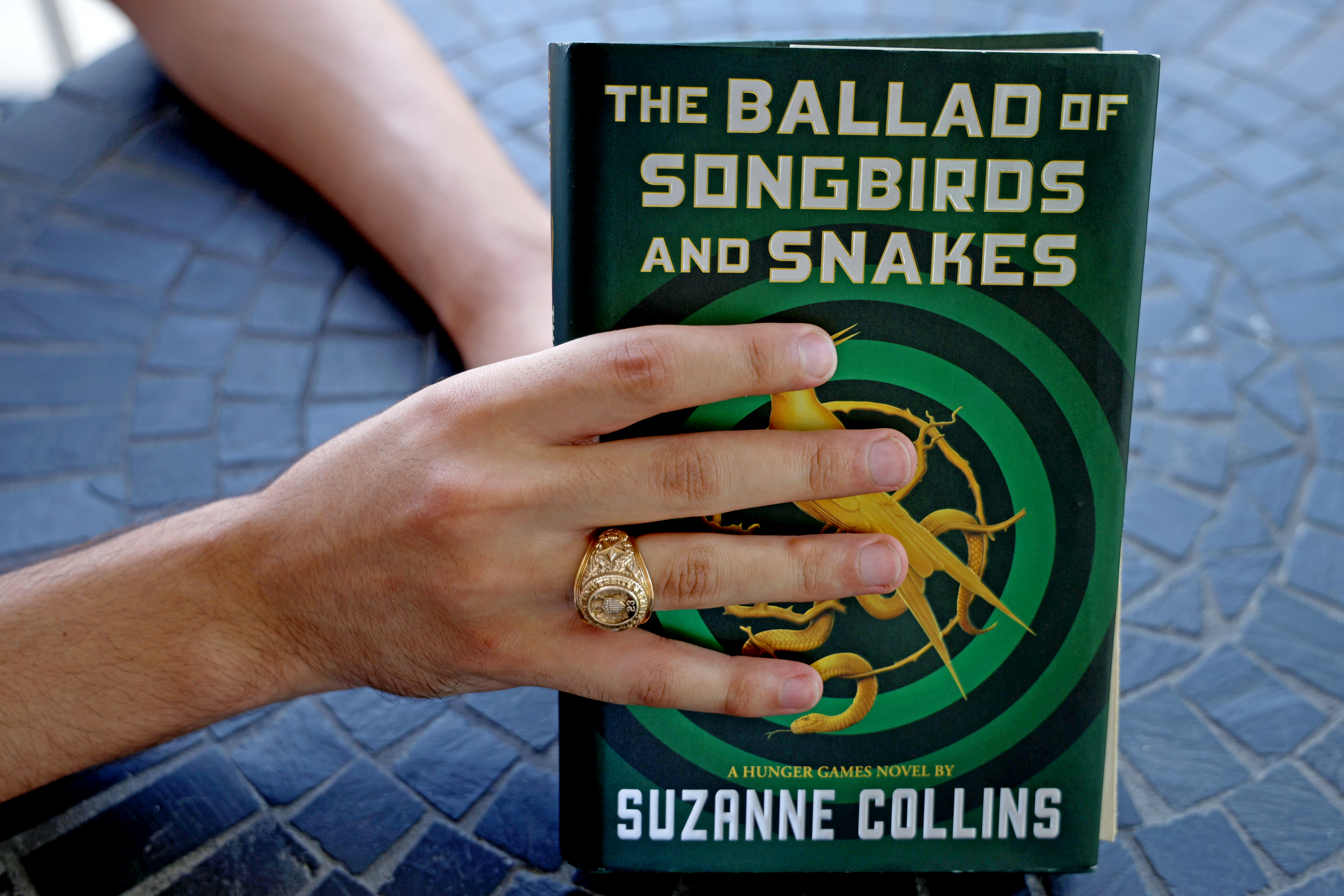

DACA recipient A.M. wears his Texas A&M University “Aggie Ring” and holds one of his favorite books. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

Then, A.M. was named valedictorian of his high school class. During his graduation speech, he took a risk and told the audience he was living in America without legal permission.

Hearing their applause, he was surprised but heartened.

Leading up to and after Trump’s 2016 election, A.M. opened up to more people about his status.

“That was kind of the awakening of: I shouldn’t have to live in fear, even though everything that he’s saying is kind of antagonizing us,” he said. “On the contrary, I should fight against it, stand up for myself and stand up for others like me.”

Always a science lover, A.M. studied microbiology at Texas A&M University and hoped to go to medical school, but only two Texas medical schools accept DACA recipients. Instead, he’s training to become a community health worker to help others who lack status get access to the resources they need.

In college, A.M. finally met other people who’d grown up as he did. He got involved with United We Dream, hosting “Know Your Rights” training sessions on campus and sharing resources for the organization’s UndocuHealth program. He plans to volunteer at an immigration center in Houston and wants to start a network to help business owners alert each other to immigration agent sightings.

DACA is the only thing protecting A.M. from deportation. He considered applying for an employment-based visa, but an attorney advised him to stick with DACA because the visa was not guaranteed. His little brother is a U.S. citizen but too young to sponsor him for a green card. The only other option for a family-based petition is through marriage to a U.S. citizen.

For now, A.M. plans to keep renewing DACA, but he’s hopeful that Congress will pass the DREAM Act. He thinks everyday Texans would support the bill even if their Republican congressmembers didn’t.

What helps him stay positive, he said, “is recognizing my worth here in the country, how much I’ve contributed to the lives of others and how much they’ve contributed to my life as well. And realizing that, yes, I might be undocumented, but that doesn’t make me any different.

“I still matter. My existence still matters.”

An application, and a life, caught in the crosshairs

A.L. has twice applied for DACA but has never been approved due to litigation that stopped the government from processing applications. (Photo by Mia Hilkowitz/News21)

The then-19-year-old psychology student made her way to the library of San Antonio College. As she settled in, a news report caught her eye: Trump had terminated DACA. The news cut deep: A.L. had recently submitted her application to become a recipient of the program.

“Everything else after that was just like gibberish to me,” said the now-26-year-old. “I didn’t feel connected to my body in that instant.”

A few years ago, she reapplied. But her application was frozen in the system after a judge deemed the program unlawful, barring new applications from being processed.

“I felt like I wasn’t worth very much,” A.L. said. “I thought: Why do all these people have opportunities and I don’t, when I feel like I’ve always worked hard since I was little to get to where I am?”

A.L. and her family emigrated from Aguascalientes, Mexico, in 1999, when she was just 9 months old. The fourth of five children and a self-described overachiever, she has always worked hard to excel, from being on the honor roll in elementary and middle school to taking classes for college credit while still in high school.

When A.L. began thinking about college, she set her sights on the Ivy League. But when she shared that dream with her mother, she got an unexpected response:

“You can’t apply to certain schools,” her mother warned. “You’re undocumented.”

The teenager then asked: “What is being ‘undocumented?’”

A.L. holds her Tau Sigma National Honor Society stole on Monday, June 16, 2025, in San Antonio. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

While many colleges allow students in the country illegally to enroll, A.L. said her family worried for her safety, given that she is the only one of the family’s children without protected status or citizenship. As A.L. watched her friends send off their college applications, she began to feel the effects of her status.

“That’s when it hits you,” she said, “that reality that you can’t do everything that everyone else is doing.”

She’s consulted with a lawyer about other ways to gain legal status; their advice was that marriage would be her fastest route. So, she continues to hold out hope for DACA, despite the uncertainty and the effect waiting has had on her mental health.

Her personal experiences drove her to study psychology in college. She hopes to become a licensed family and marriage therapist, because she wants to help others find stability – something she has always lacked.

A.L. has thought about returning to Mexico, but she said her parents brought her to the U.S. to give her a better future – and she intends to build that future in America, despite the obstacles.

“I guess you can say this is my life – it’s been my life since I was a baby,” she said. “This is where I grew up, and if I fought this hard to be here, I’m not going to give it up to go back.”

A Texan at heart considers leaving

A.L.E., a DACA holder for seven years, is one of over 500,000 current recipients in limbo as they wait to see what happens with the program under the second Trump administration. (Photo by Tristan E. M. Leach/News21)

A.L.E. was just 5 when her parents moved her family from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, to the Lone Star State. Fort Worth is home to everything she holds dear: her parents, her two younger sisters, her boyfriend and her closest friends.

When A.L.E. learned that Christmas morning in high school that she’d obtained DACA, she put down roots and pursued the opportunities her parents hoped she’d have in the U.S. She got a driver’s license and a job as a lifeguard. She went to college to study political science.

Texas is the only home she knows.

Now, she wants to attend law school in Texas so she can stay near her two younger sisters, both U.S. citizens. But with the state likely to end work authorization for DACA recipients, she wouldn’t be able to save for tuition or pay her bills. She said she’d have to go elsewhere.

“My community is here, and I don’t want to leave that because of something that a politician has decided they don’t like or does not fit into their agenda,” she said.

It remains unclear how a federal judge will implement the court ruling against DACA and work authorization in Texas. But the state’s nearly 88,000 DACA holders could face the same dilemma: Stay with their friends and families, or leave to be able to work.

A.L.E. recently learned she’s developed an autoimmune disease. She blames the stress of worrying about an uncertain future. She’s saving money and reaching out to family in Mexico, in case she has to leave the U.S. But she doesn’t have any real plan for what she will do if DACA ends.

“I don’t want to marry someone just because I’m scared I’m going to lose everything I have,” she said. “It’s also hard to get an employer to be like, ‘Yes, we’ll help you with this.’”

A.L.E. has been involved in politics for years. During her senior year of college, she interned for a member of Congress, spending much of her time focusing on immigration policy. She’s gone door to door in communities in Arizona, canvassing for United We Dream. She also campaigns for her county’s Democratic Party.

However, she isn’t afraid to call out Democrats for failing to pass the DREAM Act when a Democrat was in the White House and the party was in control of Congress. She’s cautiously hopeful that lawmakers will act under Trump. And she has no plans to stop fighting for a chance to live out her life in America.

“At a certain point, we didn’t have DACA,” she said. “We had to advocate for it. We had to go to the streets. We had to go to Congress and be like, ‘You need to give us something now. … You need to help us.’

“So I think that’s something that we need to think about – to just stay open-minded and stay hopeful and just not give up.”

News21 reporter Hannah Psalma Ramirez contributed to this story.

A protester holds a sign at the “No Kings Day” demonstration on Saturday, June 14, 2024, in Dallas. Millions of people nationwide took to the streets to protest the policies of the Trump administration, including those related to immigration. (Photo by Mia Hilkowitz/News21)